After years of resistance, oil executives are raising global-warming issue ahead of summit

Oil companies are ratcheting up their involvement in the debate over climate change as governments, activists, churches and some big investors gear up for a global summit on the issue at the end of the year in Paris.

The stated goal of the summit is to keep manmade warming limited to two degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, but governments remain far apart on how to achieve it.

Meeting such a goal will require far-reaching changes in energy-consumption patterns and likely efforts to put a cost on carbon use, many experts say. Activists have long focused much of their effort on trying to rein in the use of resource companies’ bread and butter: carbon-emitting fossil fuels.

RELATED Interview -- Mining Interest on C&C

Pope Francis is planning to weigh in on the environment in an encyclical—a letter intended to develop and explain Catholic teaching—due within the next few weeks, which has made Rome one of the focal points in the global-warming debate. Exxon Mobil Corp.recently dispatched one of its senior lobbyists and a planning executive to Rome in an attempt to brief the Vatican on its outlook for energy markets.

For years, shareholder activists have urged resource companies to curb emissions. More recently, some big investors are taking global warming into consideration in their portfolio building. The Church of England and Norway’s sovereign-wealth fund, one of the world’s biggest institutional investors, have sold off shares in pure-play coal companies.

‘We have to stop being defensive.’

At the same time, some of the resource companies’ own shareholders are pushing them to scale back their dependence on carbon-based fuels, worried about the future financial impact of heightened global-warming regulation. Oil, mining and coal companies also are anticipating rules to limit emissions that would make oil and natural gas more costly, potentially reducing demand for the fuels.

“We have to stop being defensive,” Total SA Chief Executive Patrick Pouyanné told a major industry conference in Houston last month. “In the end, it won’t be solved by diplomacy only, but by private players, economic players like us.”

Total, Saudi Aramco, Eni SpA, BG PLC, Royal Dutch Shell PLC and others have formed an industry group specifically to add their collective voice to the climate debate, and they are trying to bring other leading international oil-and-gas companies into the group.

“Business is engaged in a way I’ve never seen before,” said Rachel Kyte, head of the climate-change division of the World Bank.

Similarly, the mining industry’s “approach to sustainable development has evolved,” said Gary Goldberg, chief executive of Newmont Mining Corp., one of the world’s biggest gold-mining companies. “It still needs to be addressed globally, and you still need to come up with a global solution.”

In February, Shell Chief Executive Ben van Beurden told a group of executives decked out in tuxedos and formal gowns at an oil-and-gas conference in London that they could no longer keep a “low profile on the issue” of climate change ahead of United Nations-sponsored talks in Paris this year that could result in new global carbon-emissions limits.

“We have to make sure that our voice is heard by members of government, by civil society and the general public,” he said.

The Vatican is another important constituency. In an unusually explicit mix of the political and pastoral, Pope Francis has said he wants his encyclical about the environment to come out before the Paris climate meeting, so that it can “make a contribution” to deliberations there.

“The minute the word got out that the pope was working on this, we had a lot of people contributing,” said Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana, who heads the Vatican office in charge of drafting the encyclical. “We listened to everybody who had something to say: physicians, academicians, students; people in all walks of life, including people from the oil industry.”

The Exxon briefing took place over a small private lunch at the home of a U.S. diplomat in the U.S. Embassy to the Holy See. A second Exxon lobbyist who is based in Italy attended the meeting, Exxon said.

The meeting also was attended by Curtis McKenzie, a Canadian national with experience in finance and the oil-and-gas industry. Mr. McKenzie has had several duties in Cardinal Turkson’s office, including administrative and research tasks and media relations, all on a voluntary basis. Such arrangements happen occasionally in Vatican offices, some of which serve much like mini-think tanks.

Vatican officials weren’t present, Mr. McKenzie said. He said he isn’t directly involved in work related to the encyclical. A lay member of the Franciscan religious order and a university professor also attended the meeting, but neither has connections to the Vatican, he said.

The encyclical pointedly wasn’t discussed at the meeting, Exxon and Mr. McKenzie said. The Exxon planning official gave a 16-slide PowerPoint presentation covering the company’s broad outlook for the global industry and energy use—a talk Exxon spokesman Alan Jeffers said its executives have delivered hundreds of times this year, including to another group of legislators and government officials, on the same trip to Rome.

Exxon said that interacting with the Vatican isn’t unusual for the company. “Exxon Mobil has a long-standing relationship with the Vatican and our people have had numerous interactions with Vatican officials over the years,” Mr. Jeffers said in an emailed comment.

Exxon and others are increasingly engaged with shareholders voicing concerns about the impact of carbon regulations on the value of their assets. Their argument: If governments rein in carbon emissions, companies may not be able to extract all the oil or metal they claim as reserves.

In response, Exxon published two reports a year ago arguing that governments are unlikely to impose restrictions that will slow economic growth. That virtually assures that fossil fuels will remain valuable, Exxon says.

Rex Tillerson, Exxon’s chairman and chief executive, told thousands of executives and industry officials at a recent industry conference that “everyone agrees” that even three decades from now about 80% of the world’s energy supply will come from fossil fuels.

“We think we’re in a business the world needs,” he said. “What we have to do is deliver in a way that is acceptable to the public.”

—Daniel Gilbert and John W. Miller contributed to this article.

Write to Bill Spindle at [email protected]

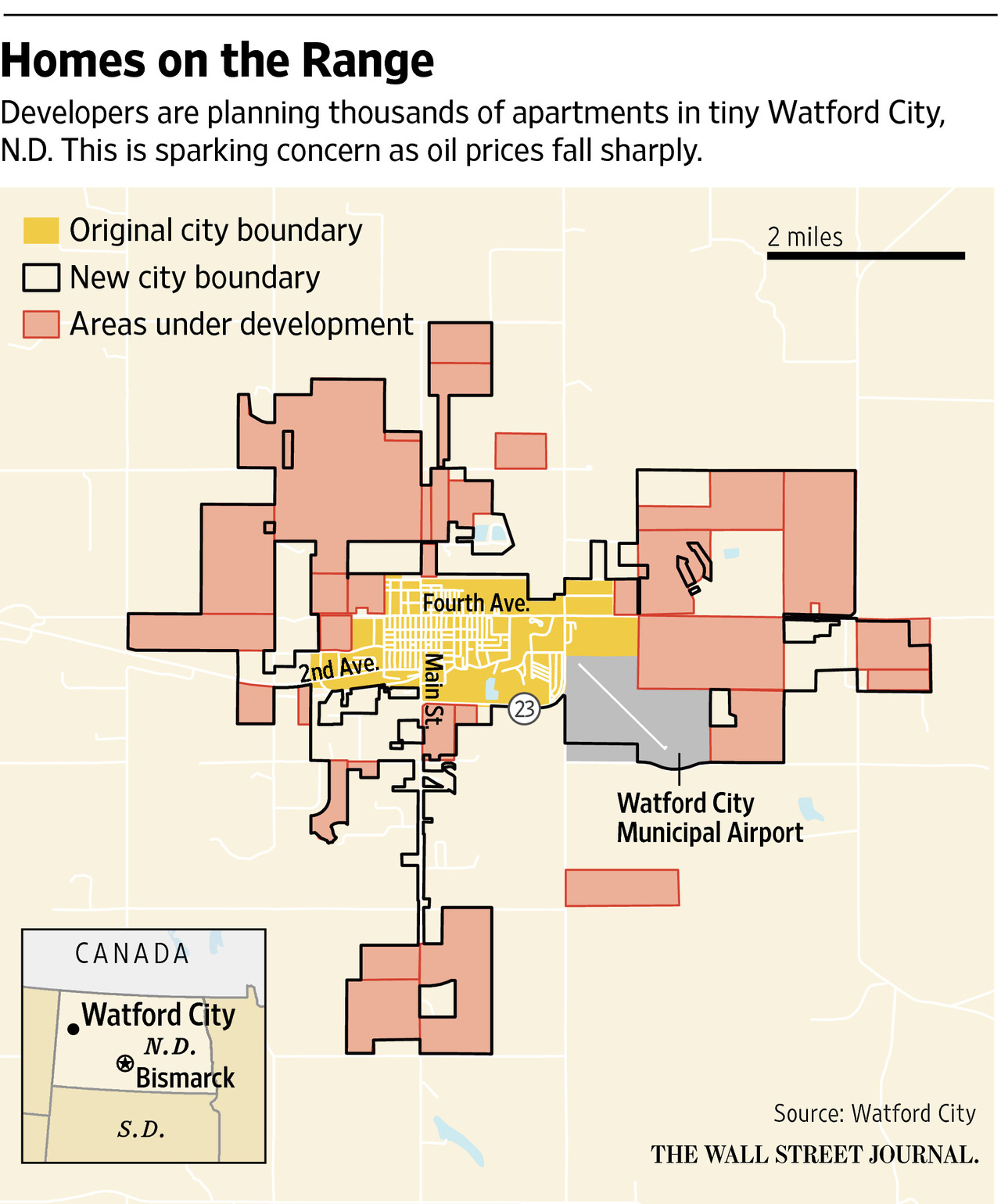

For now, Watford City and other once-tiny towns in this region of western North Dakota are still humming with construction. Developers are building thousands of apartment units and homes, hoping to see the same demand that sent rents for two-bedroom apartments soaring to $2,800 a month—more than double what landlords got before a type of oil extraction known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, took off in the area starting around 2009.

For now, Watford City and other once-tiny towns in this region of western North Dakota are still humming with construction. Developers are building thousands of apartment units and homes, hoping to see the same demand that sent rents for two-bedroom apartments soaring to $2,800 a month—more than double what landlords got before a type of oil extraction known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, took off in the area starting around 2009.

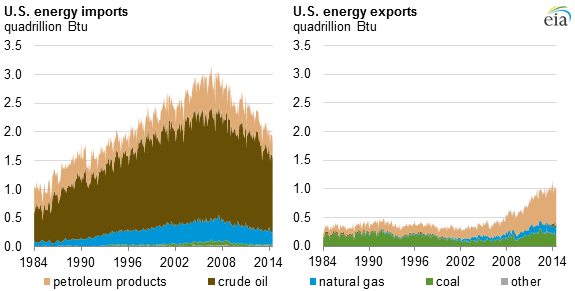

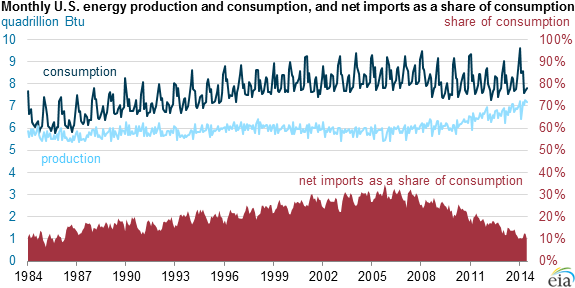

Total U.S. net imports of energy as a share of energy consumption fell to their lowest level in 29 years for the first six months of 2014. Total energy consumption in the first six months of 2014 was 3% above consumption during the first six months of 2013, but consumption growth was outpaced by increases in total energy production. These changes led to a 17% reduction in net imports compared with the first six months of 2013.

Total U.S. net imports of energy as a share of energy consumption fell to their lowest level in 29 years for the first six months of 2014. Total energy consumption in the first six months of 2014 was 3% above consumption during the first six months of 2013, but consumption growth was outpaced by increases in total energy production. These changes led to a 17% reduction in net imports compared with the first six months of 2013.